“Teachers are underpaid!” is a thing you will read on Teacher Twitter (or hear from your teacher friends who share the opinion). As a teacher of seventeen years in a wealthier district, I disagree personally. I think my union has negotiated great contracts (though not perfect, notably a few pay freezes), and I routinely enjoy high-fiving union leaders when I see them.

Many have legit beef. My sister teaches in an urban school, where her basement classroom periodically floods. The basement teachers wonder who is responsible for resolving this ongoing drainage issue—the district or the township? Is there mold growing behind the walls, putting their health at risk? Oh, and the district just announced massive budget cuts in key positions (assistant principals and building subs). She is definitely underpaid (and clearly a saint).

But a linguistic trick exposes a core fallacy of the disgruntled: the passive voice of “teachers are underpaid.” Who is doing the paying? The district, who publicly agrees to abide by a contract which outlines a clear salary schedule and educator duties. This underscores the entire debate: teachers freely chose the jobs they decry as undervaluing them. To say “I am underpaid for a position I knew would pay me X over the next five years” is to remove one’s own agency. It’s also sort of whiney.

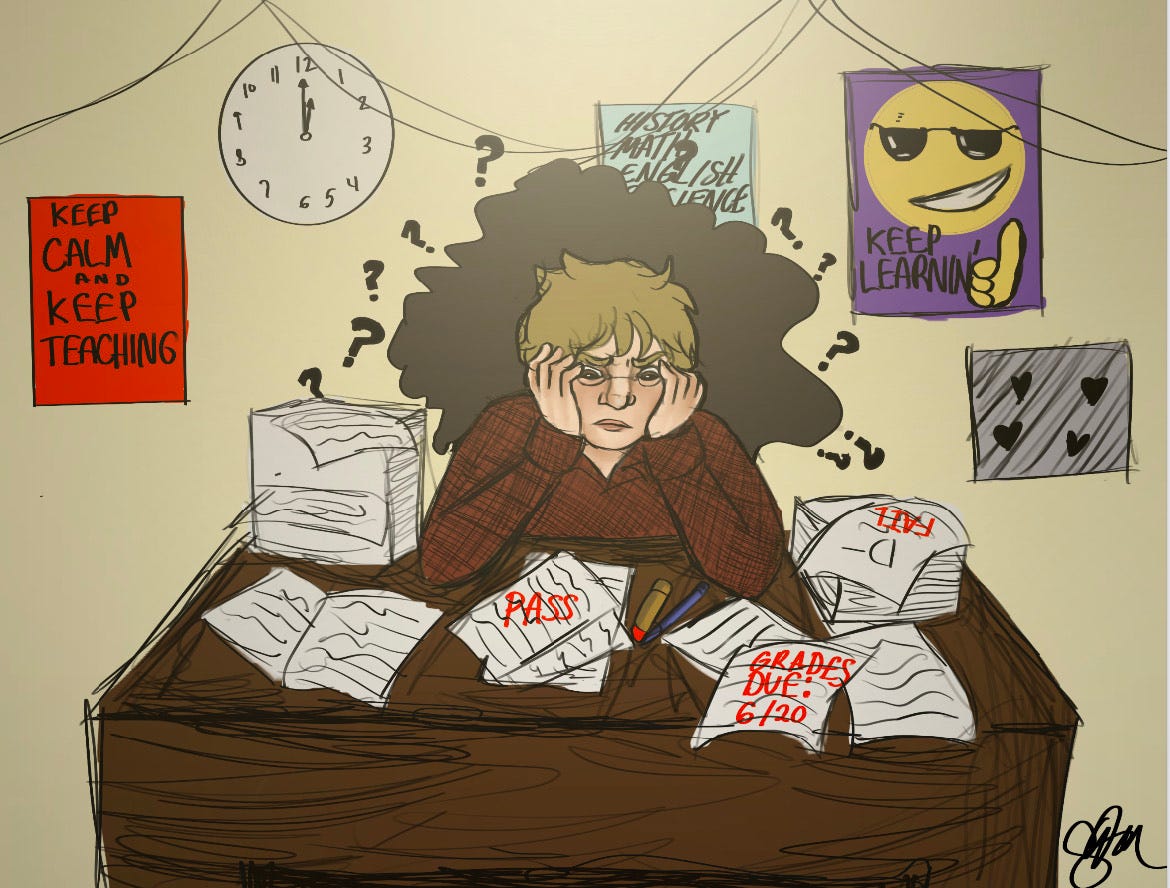

I suspect the real issue is the unknown and often untenable working conditions that accompany the teaching profession. This is a perfectly valid argument: a teacher starting at $40,000 has no idea the level of support, student needs, or extra workload required for any given year, or with increased testing stakes, future years. He or she might also be unaware of the cost of graduate courses (or extra hours) to climb the pay scale. From this comes the very fair “I am not being paid enough to do this” argument, which, while still an opinion, rings more honest. Compared to a peer, many of us are not being paid a fair wage for the insanity we deal with on a daily basis, no doubt a leading reason that teachers have been fleeing the profession in record numbers.

Okay, but still: if you don’t like your job because the demands are too great and the pay is too little, just do what every other person does—find another one. No one is forcing teachers to stay in a job in that specific district, which, by any measurable standard, is terrible. As a children’s book author, I’ve visited dozens of schools and heard many teacher horror stories—kids cursing them out, fights, no administrator support, all for less than I make. I could not agree more: you are underpaid. I would leave that job at year’s end.

Yet here’s where the “underpaid” crowd has a legitimate gripe: we teachers get kneecapped if we move districts. Unlike, say, a nurse, who can transfer whenever or even pick up a highly lucrative short-term contract, we’re stuck. Districts can start us at whatever pay scale they want, which is almost always lower. They can do this because we’re at their mercy; we want a better job, and so we’ll take a pay cut. Perhaps it’s not really a cut, when all the “better” work culture factors of the new school are in play, but financially, it’s a downgrade. Compounding any attempt to move is that teachers rarely move in large numbers, unlike, say, the financial sector. Turnover, while lately increased, is still extremely low. To move schools is possible, but poses financial hazards that most jobs don’t.

A buddy who teaches in Philly’s largest high school (driving an hour plus each way) offered this insight: “It costs too much money to get the degree and then too much money to change jobs because of the lack of recognizably transferable skills, which is sad. It keeps people stuck.” Many of us teachers were unaware of not just the “extra” stuff we were expected to do, but the wild changes in education—from standardized testing bonanzas to AI. To keep our certifications and earn more, we went into further debt to take grad classes, all while the job began to change under our feet. “The profession as a whole is in so much flux that people are trying to find explanations for why they are unhappy,” he went on, “and justifications for why they should leave.”

“But you have summers off!” some person will shout at this point, soon to be ducking as a bottle is thrown at them by the nearest educator. Yeah, we get summers off. We also deal with the behaviors of your child that you’ve refused to discipline (more on this in a future post), all while handling a room full of twenty-nine other kids, many with legally-binding learning plans (IEP, 504, ELD). Heaven help the unfortunate “average” kid who is straight up overlooked or the above-average kid who isn’t being challenged. The great irony of the “those who can’t, teach” insult is that people dumb enough to say it wouldn’t last half a day in a classroom. My students would eat you alive.

Still, the lame “you have summers off” people have a point. I chose a profession that was difficult—even if in unpredictable ways— and part of that is an eight-week paid vacation. Those are the facts. The degree to which that is a fair trade for the things I deal with is irrelevant to the fact that I knowingly and freely chose this career—or that I stay in it, whatever the pay. Teachers need to grapple with this realistic approach instead of defending their summer with “all the hours and crappy things I put up with during the year.” Every job has stress points. Most people quit if it gets too much—which they arguable should! We should also guest lecture at teaching colleges to tell future teachers what they will be facing in the real world.

A final thought: the “but it’s for the kids” argument to justify staying in an underpaid position, which many of us do. I love my students—yes, even the hard ones. Teaching is a passion as much as it is employment. But it’s also weirdly shot through with a moral whiff of America’s youth being somehow at stake if we do or don’t do X or Y. This could be pouring in the hours to make a unit or curriculum amazing (which I routinely do); this could be volunteering to lead committees (which I despise, and never do, as it sucks energy from good teaching); or it could be making up amazing acts for the year-end-talent show (literally uploading them to YouTube as I write this). But non-teachers should know that working with kids brings a strange sort of burden—we teachers “feel”, even if we shouldn’t, that these kids are depending on us somehow. This, I think, is what keeps us in underpaid positions, far too long. We feel stuck in a system, but leaving that system hurts the ones we love the most, who have the least blame, and yet will feel the biggest blow. No doubt a therapist would have something to say about the close connection to this and “cycles of abuse.”

In the end, teachers have two bad options: stay in underpaid jobs or find new ones. To glibly say “that’s the system, deal with it” ignores a foundational crack (quickening to a gulf) that threatens to swallow up the societal necessity of shaping the next generation: does anyone really think it’s “good” to pay so little for a job that’s so critical?

Or perhaps that’s the answer. Our culture does not think teachers are critical, and so they will not pay them more (or provide them more support). This is certainly the sentiment, if not the reality, in many schools. Aside from leaving an underpaid position, I see no way teachers can fight this, even if doing so means widening that same gulf.

My understanding -- from well outside the business -- is that a large chunk of the problem is that there is a lot of seniority pay, tenure, and other factors that make it difficult to transfer to a different district. So the teacher/school contract isn't really an ordinary market where people circulate between jobs (and jobs circulate between people), forcing each job to pay more or less what it's worth to the teacher. Rather, if you teach for one year at a school, you're partly paid in that year and partly in a non-binding promise of getting better pay late in your career *there* when you've built up a couple of decades of seniority. But you lose the value of that promise if you go to another district.

Am I correct here?

My “annual” contract is for 10 months so I’m not getting 8 weeks of paid vacation in the summer. Yes, my health insurance carries through the summer but salary, sick days, and personal days are based on 10 months. Admin and a small number of teachers on 12 month contracts have proportionally higher pay and additional benefits.

That said, I generally agree, I’m not underpaid. The entirely modest salary bumps are rough during higher inflation periods and the percent increases are well below normal inflation once a teacher is at the top of their salary guide, but those are known factors going in. These limitations can also be balanced by other factors depending upon the district including accumulating and selling of sick days. So again, I agree, well-negotiated contracts are plenty fair.

There is another challenge when it comes to switching teaching jobs - the loss of tenure. If tenured teachers could switch districts and have a shorter period to regain tenure in the new district then something resembling a genuine market for teaching experience and talent would likely follow.